Treaty Principles Bill: Smokescreen for sweeping change?

A guest newsletter by Melanie Nelson.

Much has been said about how the coalition government’s Treaty Principles Bill distorts te Tiriti o Waitangi. However, it could also serve as a Trojan horse, installing an extreme libertarian agenda.

We don’t know the intent driving the proposed Bill; however, many serious effects may ensue. Far from simply clarifying the Treaty principles, the proposed Treaty Principles Bill may provide politicians with access to alter our constitutional foundations and multiple existing laws – without needing to amend or repeal those laws – with potential sweeping economic, environmental, indigenous and social repercussions.

The Treaty is a red herring and a target

The wording of the proposed new ‘Treaty principles’ redefines the articles and principles of the Treaty as something they are not – a regime centred on libertarian ideals of largely unhindered private property rights, individual sovereignty, self-reliance and a one-size-fits-all approach, enforced by Government authority.

If passed, the Bill could legally and perhaps constitutionally embed a regime that gives significant weight to safeguarding those ideals – with minimal interference, regulation or affirmative action from government – at the expense of other societal or environmental values.

Any illusion of the Bill only affecting the Treaty is a red herring, distracting us from the potential consequences across the legal and political landscape – far beyond the already-serious impacts of the proposed principles on the Treaty, indigenous rights and the Māori voice.

Government continuing work on a Treaty principles referendum

The National-Act coalition agreement provides for a Treaty Principles Bill based on Act party policy to be introduced to parliament and supported to Select Committee as soon as practicable. It is expected to be progressed over 2024 and introduced to Parliament in the near future. When pressured by media, Christopher Luxon stated on 7th February that the National Party position is that they would not support the Bill past Select Committee, however he left the door ajar by explicitly noting that he was speaking as leader of the National Party and not as Prime Minister.

Associate Minister of Justice David Seymour confirmed that the Ministry of Justice is working on a referendum for the Treaty Principles Bill as part of the Bill’s development, in answers to Parliamentary written questions on 20th February and 10th April. He had also received two briefings containing advice on a potential referendum for the Treaty Principles Bill, on 14th December and 12th March.

Although the Bill will be based on Act policy, Cabinet will need to agree to its final shape before it is introduced, and that important detail is not yet available. If the other coalition parties agree to adopt the wording of the ‘Treaty principles’ tendered by Act, they would likely be enabling the Treaty to be both disinterpreted and displaced.

Far-reaching impact on existing laws

Enacting in law a new set of ‘Treaty principles’, to replace the existing common law principles, would automatically change the interpretative lens of multiple laws wherever the phrase the “principles of the Treaty of Waitangi” is used, such as in the Conservation Act 1987, the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act 2000 and the Crown Minerals Act 1991.

The result would be a legally enforceable obligation on all persons exercising functions and powers under those laws to give weight to these new libertarian ‘Treaty principles’, rather than the relationship with Māori – a radical departure from the existing norms, affecting their policies, processes, decision-making and activities.

The government recently announced a review of the Treaty principles clauses in over 40 laws, as part of the New Zealand First coalition agreement. On face value, this initiative could appear to conflict with the planned Treaty Principles Bill. However, Shane Jones indicated that this review seeks to change the focus of the Treaty clauses from the Treaty to Treaty settlements (an entirely different matter), referencing the Fast-Track Approvals Bill as an example, and to reduce the Treaty’s impact on decision-making and investment.

The consequences of each action may not be totally paradoxical. The review may result in the narrowing or removal of numerous Treaty protections from legislation. Importantly in this context, the Treaty Principles Bill, if passed, could limit the ability of future governments to restore meaningful Treaty principles clauses, or even to include them in new laws. Therefore each of these government initiatives heightens the significance of the other, of grave concern to those seeking to safeguard the role of te Tiriti, as well as social and environmental protections.

A defining constitutional act?

David Seymour is on record as stating that the proposed ‘Treaty principles’ would provide a constitutional platform for New Zealand. Indeed, it appears that the Treaty Principles Bill could be considered to be a constitutional Bill due to the subject matter of each of the proposed principles, in addition to the fact that it pertains directly to te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Te Tiriti is part of our unwritten constitution; its text has never been formally passed into law. Although the Bill is said to focus on the Treaty principles, it could access the constitutional force of te Tiriti itself.

The structure of te Tiriti is roughly reflected in the proposal – the Treaty principles that the Act Party are campaigning on are headed “The Treaty Articles” and labelled and numbered accordingly.

Given the surface equivalence between these proposed principles and the articles, the Bill can be seen to endeavour to enforce a different meaning on the original text.

We must consider whether Parliament legislating ‘definitions’ of the Treaty articles for the first time in enforceable law could constitutionalise this regime and simultaneously negate the existing role of te Tiriti and its principles.

Principles recast to be something they are not

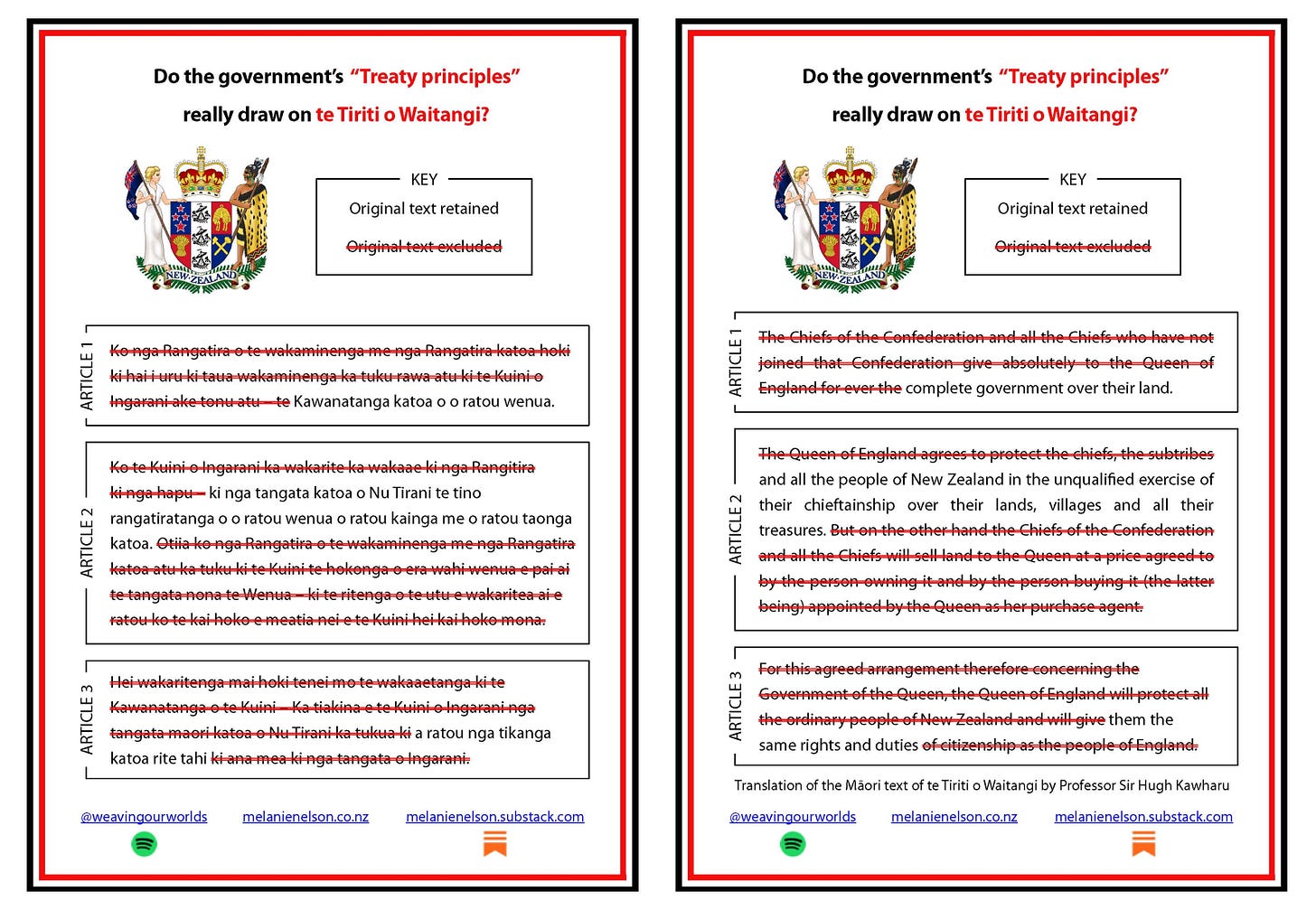

Most of our current Treaty principles – which include partnership, good faith, autonomy, governance, reciprocity, active protection, informed decision-making, mutual benefit, equity, options, development and redress – are notably absent in the proposal.

The suggested ‘Treaty principles’ have no true origins in te Tiriti or the Treaty. They make no mention of Māori, with whom the agreement was made.

Minimal part-phrases are cherry-picked from the Māori text of te Tiriti, decontextualised linguistically, historically and culturally, and recast with new meanings.

The resulting ‘Treaty principles’ crumple under scrutiny:

“Article 1: kawanatanga katoa o o ratou whenua

The New Zealand Government has the right to govern all New Zealanders”

The term “New Zealand Government” typically refers to the Executive branch of the government. This proposed principle entrenches the authority of the New Zealand Government – to both enforce the ideals expressed in the other two principles and potentially to govern without civic participation. It may affect the balance of power and restrict the judiciary. It also elevates the Crown’s power in relation to Māori, which is inconsistent with the guarantee of tino rangatiratanga in te Tiriti.

“Article 2: ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou whenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa

The New Zealand Government will honour all New Zealanders in the chieftainship of their land and all their property”

This erases the true meaning of tino rangatiratanga from Article 2 and introduces the concepts of the New Zealand Government and all New Zealanders, and the libertarian ideals of individual sovereignty and largely unhindered property rights. Article 2 of te Tiriti is not about these things; it guarantees the tino rangatiratanga of Māori.

“Article 3: a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi

All New Zealanders are equal under the law with the same rights and duties”

This is a seismic shift from equity to individual self-reliance, and from Māori to all. It could also delegitimise differential treatment according to need and redistribution. Article 3 of te Tiriti is not about the equal individual rights and duties of all New Zealanders; it gives Māori the rights of British citizens, additional to the above preservation of pre-existing Māori rights.

Tricky, not Treaty

If the Bill is passed, this ‘recasting’ of what is said in te Tiriti could lead to political preferences becoming embedded in an inaccurate interpretation of the Treaty, bypassing its legal, linguistic and historical realities.

Although Parliament has the power to legislate, for example, that all dogs are cats, that does not make it true that dogs are cats. Likewise, Parliament could legislate that the Treaty principles are now based on a regime of Government authority, property rights supremacy, individual sovereignty, self-reliance and rigidly homogenised systems, in place of the relationship with Māori. It would be inherently problematic to have such fiction enshrined as legal fact in our laws.

Additionally, future governments could amend the law with their own preferred values, putting the Treaty on a perpetual political roundabout – causing instability legally and possibly constitutionally, as well as in the partnership with Māori.

Given the constitutional standing of this Bill, it could even be expected that the government might consider entrenching the Act, making it harder for future governments to amend or reverse it. A law can be entrenched by a simple majority, especially when it is of a constitutional nature or a public referendum is held, meaning that the law can then only be amended or repealed by a parliamentary super-majority.

National sweeping changes, from just one Act

Treaty principles clauses have different roles and effects in different pieces of legislation. The Bill’s potential consequences across the board could be extraordinary. Under current legislation, the RMA and Conservation Act would require persons acting under them to respectively “have regard” or “give effect” to the remodelled ‘Treaty principles’ of largely unhindered property rights, individual sovereignty and the same treatment for all, enforced by Government authority.

Not only would the role of Māori under these laws be removed, but most likely also the special voices of NGOs and local communities. The supremacy of those granted property rights to develop and exploit resources, including intellectual property, would become the guiding lens for interpreting and administering conservation legislation, along with the Government’s authority to enforce this. This could lead to extensive irreversible destruction across the conservation estate, with corporate elites taking judicial review proceedings against future governments if their business aspirations were blocked.

In resource management matters, largely unhindered property rights could mean that wealthy property owners are able to develop their land as they wish, without the participation of surrounding communities and tangata whenua in decision making, and outside the protections offered by environmental limitations and mitigation.

The jurisdiction of the Waitangi Tribunal is also defined by acts or omissions which are inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. As well as fundamentally impacting the Tribunal, it is possible that the proposed change of ‘Treaty principles’ would even circumvent claims and settlements of historic and contemporary breaches of the actual Treaty principles.

The meaning of equality under the law often depends on the interests of those expressing it. In this third proposed principle, the libertarian interpretation is most likely – that positive discrimination, state intervention and redistribution are not allowed. Equality under the law thus protects the individual’s right to preserve their wealth without infringement. At both constitutional and legal levels this has profound implications for taxes, welfare, social housing, health and education.

The “same rights and duties” for all New Zealanders could mean that targeted action for vulnerable people, marginalised communities and ethnic minorities is delegitimised, and that ethnic, advocacy and interest groups are not necessarily afforded civic participation.

This Bill would usher in a new era where all understandings are up for negotiation – opening up great legal unknowns and drastically reducing Māori rights. Expensive litigation on the meanings of words and phrases that have long been settled could give rise to substantial uncertainty.

The suggested ‘Treaty principles’ are antithetical to the text and spirit of te Tiriti o Waitangi. Their outcomes are hard to predict or fathom, as the proposal is such a distortion of what has gone before.

We all need to act for our Treaty and this land we share.

Melanie Nelson

www.melanienelson.co.nz | melanienelson.substack.com

Melanie Nelson (Pākehā) is a licensed Māori language translator and interpreter, and a consultant, coach, educator and writer on cross-cultural issues.

She specialises in advising on the application of te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Treaty principles to conservation and environmental issues, and in policy and legal translations.

Melanie is a graduate of Te Panekiretanga o te Reo Māori | Institute of Excellence in the Māori Language and holds a Masters in Māori Language Excellence – Te Tohu Paerua o te Reo Kairangi.

Her podcast, Weaving our Worlds, seeks to foster mutual understanding between peoples in Aotearoa.

You have to acknowledge that this is a really cunning plan, it takes a bit of boomer racism but applies it to the corporate agenda. Thank you Melanie, a great exposition.

A long time friend asked me last week what I thought of the "Maoris' taking over NZ and having their own parliament". I was a bit dumb-founded to be honest. She has lived in this country, having moved here to escape persecution from political change in her birth country, but not once has she taken the opportunity to understand the history of this country she now calls home. Unfortunately, she shares much in common with many other people who immigrated here because they thought it was a nice little piece of [white] colonial England.

I compare that to some other much closer friends who have been actively seeking to learn the real history of Aotearoa, our customs and our reo. Theirs has been a much richer journey - not one of fear from ignorance - but filled with new knowledge, respect and new relationships with their manawhenua and tangata tiriti friends.

There is real evil at foot behind these proposed changes - one which calls us to raise our heads above the populist cry - one which challenges us to move beyond our privileged racist rampart. Because beyond that is a place where NZers can indeed share a journey of healing, and understanding - one towards ultimately a new constitution that celebrates our uniqueness and not perpetuates the colonisation which has forged division though the fabric of Aotearoa.